An Interview On Special Education With Pamela Guest, Chief Editor At IEP Magazine

Pamela Guest is the Founder and Chief Editor at IEP Magazine. More importantly, she is one of us, a parent of a dyslexic. She struggled throughout her son’s education, just like us. She had to learn the ins and outs of the system on her own with little to no support, just like us. As my path crossed hers on our journey to help others with the steep dyslexia hike, our common goals brought us together. Education is her passion and this is my interview with her.

Q. What do you think is the most pressing issue related to special education in schools today?

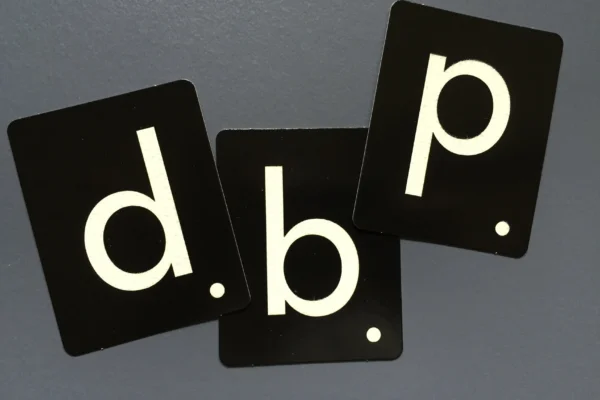

A. The issues and challenges faced by struggling readers, and more specifically students with dyslexia, impact up to 1 in 5 students in every classroom. According to the NIH, dyslexia affects 80-90% of all individuals identified as learning disabled and represents the largest group of school-aged children who receive special education services. It is identifiable with 92% accuracy, at ages 5 ½ to 6 ½ and the reading failure that is associated with dyslexia is highly preventable, through direct, explicit instruction in phonemic awareness when it is identified early. The problem is that there is no systematic process in place to ensure that students with dyslexia are identified early or even at all, and no consistent method of intervention for those few who are identified. Even after the US Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services issued a “Dear Colleagues” letter, in October 2015, with guidelines to local and state education agencies urging school systems to say and use the words dyslexia, dysgraphia and dyscalculia, most school systems have not taken action to correct the misinformed policies and procedures that have resulted in reluctance to address the problem. In an arena where labeling students has been controversial one might ask why there’s an organized push to say the words dyslexia, dysgraphia and dyscalculia. These words are so important because they drive appropriate instruction for those students who need it.

Without sweeping changes to the methods used to teach students to read and to the training of educators who provide services to these students, reading failure will persist and continue to impact outcomes for a large group of students. Of children who display reading struggles in the 1st grade, 74% will be poor readers when they get to high school and into adulthood unless they receive informed and explicit instruction.

Reading failure poses far reaching impacts on society including the costs of underemployment, remedial education & workforce training, and welfare. 85% of all juveniles who interface with the juvenile court system are functionally illiterate. Low literacy is so strongly related to crime that the phenomenon has been labeled the “School to Prison Pipeline” with 70% of prisoners falling into the lowest two levels of reading proficiency as evidence.

Q. What inspired you to become involved in efforts to address this issue and any others?

A. My younger son struggled with spelling, reading comprehension, and math throughout his school years. I had often inquired about the possibility that he might be dyslexic but my inquiries were repeatedly dismissed and no effort was ever made to investigate my suspicions. I had confidence in my son’s educators as professionals in their fields and I proceeded to push him harder and urged him to apply himself to reach the levels of success that his educators implied he was capable of achieving without intervention. They were wrong. Unfortunately, Dayne’s dyslexia was not identified until two months before high school graduation. I was overcome with feelings of guilt that I hadn’t known to push harder to confirm my suspicion, anger that my intelligent and capable son had struggled tremendously all those years without adequate support, and frustration that once his learning difference had been identified as dyslexia, his educators knew very little about what to do to help him. His confidence and self-worth suffered terribly as he was repeatedly told that he wasn’t trying hard enough and when he did try harder and worked earnestly to apply himself, there was little to no improvement. If I had known more about the processes and laws that protect students with learning disabilities and the processes that are outlined to help parents to ensure their children receive a Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) I’d have probably acted more diligently and confidently to get my son identified earlier and to fight for the proper services. I’ve decided to make every effort I can to help other parents to understand the process and to be better prepared to advocate for their children. In addition to my work with advocacy groups and as a consultant to parents, I designed IEP Magazine to be an easy to use reference and guide that parents can refer to as needed, share with others, and most of all, read without feeling overwhelmed by the information. I want the magazine to provide a positive and uplifting venue for sharing information and celebrating the unique abilities of student’s who just happen to learn differently.

Q. What concerns you the most regarding special-education-student’s needs and services?

A. Services and approaches can vary from one system to another and even from one school to another within the same system. Working with groups like Decoding Dyslexia Maryland (DDMD) and my local Special Education Citizens’ Advisory Council (SECAC), I’ve heard stories about the inconsistencies that parents face throughout school systems. Granted every student’s needs and approaches should be different, but basic services, guidance, and information should be consistent throughout systems. A parent shouldn’t have to face uncertainty for their child’s IEP if they move from one school to another either in the same or across state or district lines and the services they receive shouldn’t vary in different environments.

Another concern, which is highlighted by my own experiences, is that parents don’t have access to directed, specific, and simplified resources to help them advocate for their children. Sure, there’s loads of information out there and school systems make much of it available to parents through resource centers but availability is not enough for these parents and here’s why:

▪ Many parents don’t know to identify/associate a serviceable learning difference/disability when they see their child struggling so they don’t seek help or they don’t know what kind of help they need.

▪ These are parents who more than likely already have more on their plates than they can handle and don’t have time to muddle through tons of new information and unfamiliar resources.

▪ Since heredity is a big factor for many learning differences, parents often share a similar neurodiversity with their children which can make the effort to research and advocate even more daunting for them.

Parents need consistent, reliable direction from school systems that they can trust to tell them what will result in the best outcomes for their children.

Q. How would you describe the ideal classroom/education environment?

A. Ideally, all educators, administrators, parents and other educational support personnel would operate with intention and understanding of a guiding paradigm that all children can learn and that all students matter. Instead of focusing the bulk of resources and attention on the high achievers alone, systems would target comparable resources on ensuring that strugglers receive the services and appropriate interventions to make reasonable progress toward learning goals. In the ideal education environment, the growing rate of reading failure that exists in the United States would be treated as a crisis and given the urgent and immediate attention it deserves.

Categories:

Share This:

Related Post

Search

Check Our

Books

As children learn to read, decodable books become an important part of the learning process.

Have A Question?

We’re happy to answer your inquiry to us.